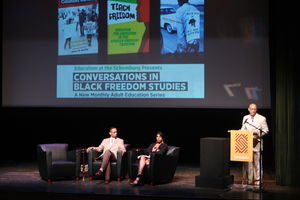

Conversations in Black Freedom Studies is a monthly roundtable discussion at the Schomburg Center with authors and experts in Black history. Held on the first Thursday of every month from 6:30-8:30pm, these conversations focus on a theme --from the Jim Crow North to the Black Panther Party, from educational inequality to the Black Arts Movement. They are geared for New York City teachers, parents, students, scholars, activists, and policy-makers. Black Freedom Studies has introduced a new paradigm for research and scholarship on the long Black revolt, challenging older conceptions of geography, leadership, ideology, culture and chronology to deepen popular understandings of the scope of the Black freedom struggle. With the closing of a number of black bookstores, there are fewer spaces where a diversity of people can gather to hear and discuss new scholarship in African American history. CBFS aims to begin to fill that need.

One dimension of the series is the significance of the intergenerational findings that have emerged in the research. In other words, the new paradigm suggests a dramatically different chronology in Black Freedom Studies, including at least two generations. For instance, Amiri Baraka’s mentors included not only Sterling Brown and Margaret Walker from the Popular Front generation but also Langston Hughes from the Harlem Renaissance.

Second, another aspect of Black Freedom Studies is the importance of the Harlem Grassroots Intellectual Tradition. In other words, for far too long we have neglected Malcolm X as a working-class intellectual alongside the fact that Malcolm X was representative of a grassroots intellectual tradition that predated Antonio Gramsci. The work on Hubert Harrison, the Socrates of the Harlem Renaissance, and the use of the Negro World as a vehicle for a mass self-education movement provides another important window into that grand Harlem tradition. That tradition of mass self-education was the groundwork for the “Each One Teach One” practices in the Black Arts Renaissance and the Black Power Movement with its countless liberation schools, student study circles, museum, libraries and salons. These discussions may be helpful to teachers, parents and students facing the challenges of austerity policies.

A third dimension of Black Freedom Studies is the promising emphasis on culture, centering on the Black Arts Renaissance. Ironically, Harlem has been grossly neglected in the new Black Arts Movement scholarship. And that neglect is distorting the contours of that research. We should take advantage of the pioneers and veterans of the Black Arts Renaissance in Harlem that remain available for roundtable discussions. If those conversations are recorded they might serve as primary sources for the scholarship to come. Sam Anderson, Jitu Weusi, Ted Wilson, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez are close at hand. And we should take the opportunity to consider the Nuyorican Arts Renaissance that flowered at times alongside and at times within the bosom of the Black Arts Movement. Felipe Luciano can shed light on the working of the Last Poets from that vantage point; and of course, the rest of the remaining Last Poets should be at the center of such a roundtable. Furthermore, Askia Toure is not far away and he was also a pioneer in the Black Arts Movement alongside Lou Gossett and so forth. Harlem was the home of Langston Hughes who seems to have cultivated the groundwork for many features of the Black Arts Renaissance, including its international character. And thus far we have neglected important figures like Elombe Brath who political and cultural work in black culture and consciousness began to flower in the 1950s, attracting many African liberation leaders to the bosom of Harlem. In fact, next year will mark the 50th anniversary of the publication of Blues People; and when I organized the 40th anniversary symposium at Sarah Lawrence College the response was overwhelming.

A fourth aspect of Black Freedom Studies in the importance of political activism and public policy alternatives in the Black Revolt in the Jim Crow North. Johanna Fernandez has highlighted the way that the Young Lords used mass media to dramatize long dormant public policy problems like lead paint to make crucial changes. Of course, the Young Lords were “in the tradition” of SNCC and the Civil Rights Revolution. And we could not miss an opportunity to talk about Brooklyn and the Bronx CORE and so forth. From the citizenship schools to the liberation schools, Black Power aimed to train generations in not only self-worth but also self-governance.

A fifth characteristic of Black Freedom Studies its attention to economic struggles, captured in several anthologies such as The Business of Black Power and Black Power at Work. In many ways, this is the case of the genius of Black Labor that remains untold. Furthermore, we might also consider the rekindled debates about the nature of internal colonialism in that venue.

A sixth feature of Black Freedom Studies is strategic importance of women’s leadership and the organizing tradition. And there is some phenomenal new work on that subject, including not only Sisters in the Struggle but also Want to Start A Revolution: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle?

A seventh aspect of Black Freedom Studies is rethinking Malcolm X. Given the controversy and Pulitzer Prize for Manning Marable’s recent biography, there is no shortage of important discussion on this subject. Of course, Malcolm X is at the center of rethinking Black Power; so the conversations that fashion some basic intellectual consensus on that research agenda is essential. With the Malcolm X papers at hand, there is no place better suited for such conversations than the Schomburg.

An eighth dimension is that of Black Internationalism and no community is better positioned than Harlem to appreciate the fact that the local is also simultaneously international. Michael West edited From Toussaint to Tupac: The Black International Since the Age of Revolution. Brent Hayes Edwards has made a major contribution in The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism. And Tyler Stovall complements that conversation with Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light.

Finally, since this is the fortieth anniversary of the 1972 Gary Agenda, we might consider some public policy and self-governance conversations about the contours of the National Black Agenda then and now, including the Harlem Agenda for 2012 and the future.